On the 27th March 2018 I visited the Michael Hoppen Gallery to see the Daido Moriyama exhibition there. This was a decision I’d made as I had written about Moriyama in some of my critical review. Although my critical review had been well received, my tutor had some comments concerning my observations about Moriyama’s work. Therefore I thought it would be a good opportunity to see some of Moriymama’s work in person. Then I could make informed amendments to my critical review based upon visiting the exhibition(s) in person.

It seemed that subject was all important to Moriyama, however the high contrast, often grainy black and white medium could not be ignored. The photographs on show still clearly referenced the world they depicted but the overall effect for me was one of disoriented otherworldliness which the black and white medium helped to back up. Some of the photographs were sharp and quite clean (not much graininess) while the majority conformed to the ‘are, bure, boke’ – grainy, blurry and out of focus characteristics which defined the left-wing group of photographers Moriyama joined in the 1960s – (Scaldaferri, 2017). This inconsistency left me somewhat confused; while Moriyama was famous for appearing in the Provoke magazine for precisely these reasons (are, bure, boke), some of the photos in the exhibition went against this trend.

However, what did remain consistent was the high contrast evident in each photograph’s finish which was a trademark of Moriyama’s process. This as well as the disconcerting subject matter (stray dogs staring at the camera, seedy images from Tokyo’s underworld and grabs of American culture in Japan) tied the exhibition together into something weirdly satisfying.

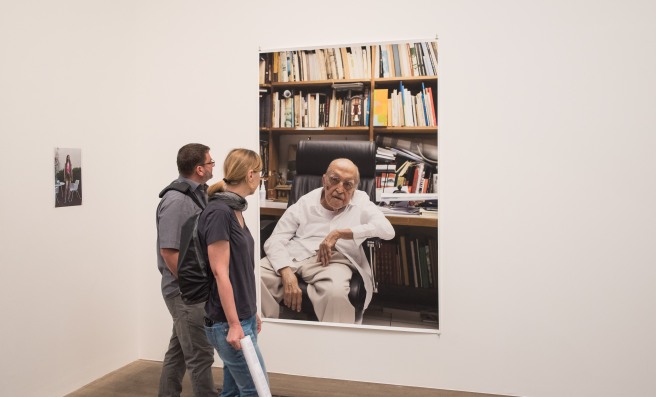

Then on the 10th May 2018 I took it upon myself to visit a larger exhibition in which Moriyama’s work appeared as a feature of many photographers’ work displayed together. The exhibition was at the Barbican and was called Another Kind of Life. I found the exhibition as a whole to be very interesting and eye-opening in places. I enjoyed some features more than others and the one which stood out most to me was Jim Goldberg’s Raised by Wolves. Here he used similar to my eyes strategies and techniques as his Open See exhibition.

When I arrived at Daido Moriyama’s Japan Photo Theatre section, I was surprised to find a very similar layout of the photographs and the way they were framed compared to the photographs in the Michael Hoppen Gallery. I realised later this was probably intentional as both exhibitions were on at the same time. However, I liked the way the frames were all black and they tessellated so that there were no gaps in between the photos. I found this style quite appealing and in my opinion went well with Moriyama’s high contrast, ore, bure, boke look. Again the photographs appeared as snapshots at first glance but the subjects and aesthetics pointed towards something different. Also I found within the context of Another Kind of Life exhibition the work fit in well as the viewer gained insight into the world of people on the margins.

I had been aware of the popularity of Moriyama in Japan and that the had influenced a large number of young Japanese photographers. I was therefore pleased to see that another photographer appeared at Another Kind of Life who had been influenced by Moriyama. His name was Seiji Kurata. Although he had been influenced by Moriyama and it was black and white, I found his work to be very different aesthetically. It was much more considered at the time of shooting and the black and white treatment was much less harsh with less contrast. There was stilll lots of contrast but it contained grey midtones and things appeared sharper and more in focus. I liked the work of Kurata and thought he had managed to develop his own style, far from copying the aesthetics of Moriyama but instead using edgy subjects reminiscent of the person he was influenced by.

Seeing a variety of Moriyama’s work in person and some of the generation he influenced left me much more informed about the aesthetics and subject matter Moriyama concentrated on. His photographs were always edgy and the subject was paramount to his way of working. However, he had developed this edgy, distinctive high contrast black and white aesthetic which for me reflected well the state of mind he was in as he roamed the streets of Tokyo looking for a subject which captured his imagination.

References:

Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins (2018). Barbican Art Gallery [Exhibition] 28 Feb – 27th May 2018.

Daido Moriyama (2018). Michael Hoppen Gallery [Exhibition] 22 Feb – 7th Apr 2018.

Scaldaferri, G. (2017). Discover The Captivating Work Of Acclaimed Japanese Photographer, Daido Moriyama. [online] Culture Trip. Available at: https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/daido-moriyama-the-father-of-street-photography-in-japan/ [Accessed 16 May. 2018].