I observed Short described the study of signs (semiotics) in a clear and concise manner, without being either too pedantic or complicated. She compared the dyadic and triadic systems for signs of de Saussure and Pierce respectively, for which Pierce used an additional element. Even though de Saussure’s model was easier to grasp, I felt that Pierce’s model satisfied all aspects of any sign’s reading. This was because it introduced the ‘object’ and the ‘interpretant’ in place of just the signified.

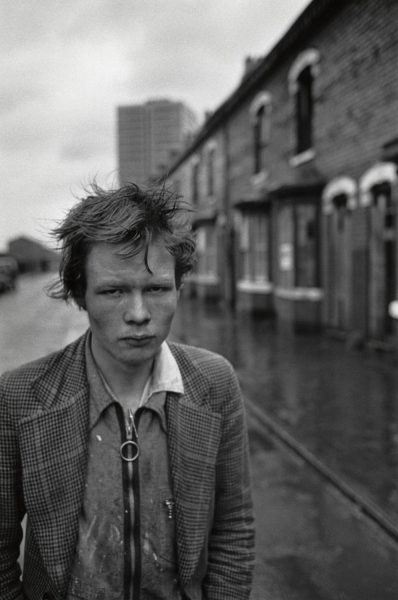

Once aware of how to recognise a sign in photography, it is important to be clear what kind of a sign it is. There are three types – symbolic, iconic and indexical. Indexicality in photography interested me the most as this property is intrinsic in every photograph. It means its there-ness – it is a part of something that happened and was recorded through light by the camera. This differs from the symbolic (where something represents something else) and the iconic (something which is perceptibly similar). Reading about the various types of signs did make me wonder whether they could be used in combination. Because indexical signs could be apparent within a photograph as well as be the photograph itself I wondered what the implications of an indexical sign appearing on an indexical photograph would be. Would the effect be like a double negative or compound the indexicality to the viewer?

Signs give extra information for the photograph to be read as the photographer intends. In this way they act as a visual metaphor, reading to the viewer pointers for meaning to be inferred. They can be subtle and unobtrusive or fill the entire photograph. They can also be a mood in the photograph so not something tangible. Ways I could envisage signs appearing in the photograph as visual metaphors after reading Chapter 5 of Context and Narrative would be:

- a simple object out of place or unusual in the context of the photograph which signified something more

- the use of focus where sharply focussed symbolises in the present while out of focus in the background is more distant and of the past

- a visually recognisable sign or symbol appearing high up in the frame of the photograph standing for power or authority

- lighting in the photograph creating a pointed mood because of the time of day which lends to the subjects of there photograph

Implementing signs into photographs I would imagine is easier if the photographer has time/inclination to construct the photograph. Because a lot of documentary is unconstructed where the photographer has to work quickly it becomes harder to think about which signs should appear where in the photographic frame. Yet this placement can give the signs extra meaning or none at all if left out of the frame. Short alludes to this in Chapter 5 and gives some pointers as to how to work with this – ‘If the photographer is clear as to the function, purpose and intention behind the photographs, these [on-the-spot] decisions are easier’ – (Short, 2011). For this reason, I would think it is very important to have a clear rationale or concept behind your images beforehand so that you can implement the signs as you see them.

References:

Short, M. (2011). Context and Narrative. 1st ed. Lausanne: AVA Publishing SA, pp.120-141.