I have been asked to read and make notes on ‘In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography) by Martha Rosler. I must admit this was particularly hard reading for me. The essay was quite long but more pointedly it wasn’t very flowing with the language used complicated. In one sense this was good practice because it would bring me up to speed with the documentary terminology but on the other hand I didn’t feel I learnt that much from the essay apart from a few key points:

Right from the outset, I found Rosler hints that documentary as it is widely known is all but gone from contemporary practice – ‘What remains of it?’ – ‘It’ being documentary photography. She goes on to assert: ‘Documentary … preceded the myth of journalistic objectivity and was partly strangled by it.’ – (Rosler, 1992). Apart from suggesting documentary as it was known had largely changed, this last quote embodied much of what I was coming to realise about photography in general. Including documentary; photography is subjective because it is the photographer’s interpretation of what they are seeing that informs the viewer. While it is true there are more objective approaches – Bate’s example of August Sander where he used typographical portraits springs to mind – ultimately they are always subjective results.

Documentary, as it was known, was comparatively futile in enabling positive change in Rosler’s examples because it was an exchange of information about less privileged people to another, more socially powerful group who didn’t want to undermine their own wealth. Instead Rosler argues intervention in the real world outside of the media was more constructive in enabling positive change. For example Cesar Chávez with the Farm Workers’ Organizing Committee.

My next point about Rosler’s essay would be concerning ‘It is impolite or dangerous to stare in person’, which she suggests, ‘as Diane Arbus knew when she arranged her satisfyingly immobilised imagery as surrogate for the real thing.’ – (Rosler, 1992). This for me implies there is a kind of mental, subconscious block induced between reality and photography where the viewer loses their inhibitions to gaze at what may alarm or discomfort them when looking at the person in a photograph. The viewer is still seeing – though through the image – because they recognise the subject through it as part of a photograph they are therefore ‘safe’ to look at for as long as is wanted. Because of this, in my opinion, the subject then becomes more distant and objectifiable.

Perhaps for this reason it is justifiable then that the photographer ‘who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay, or combinations of these and saved us the trouble’ – (Rosler, 1992) should be accredited for their efforts. They as the taker photographer provided us with a platform to stare at, through photographs, the people and conflicts which reminded documentary viewers the realities of life (although not necessarily how to relate to them or avert them from happening respectively).

‘The subject of the article is the photographer.’ – (Rosler, 1992). This struck me as a bold statement from Rosler I partially agreed with. I had been convinced for a while that the subject of the photograph or the photograph itself were all that mattered as the eventual outcome of photographs being taken. Then I was sure it was how photographs related to each other and other forms of media (their context) as well as the photograph/subject that mattered. More recently I had started to come to the conclusion that the photographer, their relationship with the subject and viewer was another key aspect of photographs ‘mattering’. Sometimes I felt the photographer’s relationship with the subject could be more important than the composition/lighting of the photograph. The statement above somewhat reinforced this understanding I was beginning to grasp although more forcibly than I agreed with. It seems that often the photograph/photographer is more important than the subject, at least in documentary. Rosler then puts this thought to discussion by examining the interesting case of Florence Thompson, the subject of Dorothea Lange’s famous Migrant Mother (1936), where the photograph was seemingly more important than the subject’s real self. ‘Are photographic images, then, like civilization, made on the backs of the exploited?’ – (Rosler, 1992), made me think how the image world, while not necessarily bad, is ambivalent towards those it uses much like reality. However, by ‘exploiting’ those it uses in the image world, photographs help sometimes on a collective level in the real world.

I had become more aware that photography was intrinsically connected to the world outside of photography in that by having an interest in political issues for example in the outside world, the photographer could better inform their photographic practice. However, before reading Rosler’s essay I was not aware that political sides could affect the reading of photographs. On the one side the ‘left’ were guilty of undermining the integrity of the image by pushing for transparency of the real world on to the image world. For example Walker Evans’ subject Allie Mae (Burroughs) Moore was rephotographed by Scott Osborne much later but this time using her real name. On the other hand, the ‘right’ attempted to use photography to illustrate the divide between classes and equality. They did this by isolating ‘it within the gallery-museum-art-market nexus, effectively differentiating elite understanding and its objects from common understanding’ – (Rosler, 1992). One consequence of doing this I presumed was that the divide would grow further. All of this meant that the real meaning the photographer intended to convey behind the photograph was being undermined by political sides afterwards.

Rosler goes on to attack John Szarkowski for his passivity of the Vietnam war which was happening when he wrote of a new generation of photographers who constituted a more personal attitude and with relation to commonplace people in the more immediate society around them. I partly agreed with Rosler on this attack because the way he put it: ‘They like the real world, in spite of its terrors, as the source of all wonder and fascination and value’ – (Szarkowski, 1967), was quite pacifying of the terrible things that were happening in the world. However, I also felt that by undertaking projects which the photographer felt was local to their passion and place of living, they would be able to form a better relationship with their subject(s). Therefore Szarkowski’s assertions in his introduction to New Documents in 1967 were not totally unfounded. However, Rosler also states that under Szarkowski’s influence Garry Winogrand refused to accept responsibility for his photographs, claiming that: ‘all meaning in photography applies only to what resides within the “four walls” of the framing edges’. This was in direct contradiction to the work of Robert Frank who Rosler compares Winogrand’s work with. Where Frank based the presentation of his work on the photographs as a purposeful series, Winogrand approached his own work from a purely modernist stance as all meaning came from within each photograph. In this respect, Szarkowski’s comments in his introduction to New Documents made little sense if the ‘new generation’ of photographers with more personal motives for their photographs wanted to affect the world immediately around them meaningfully with the same attitude as Winogrand for example.

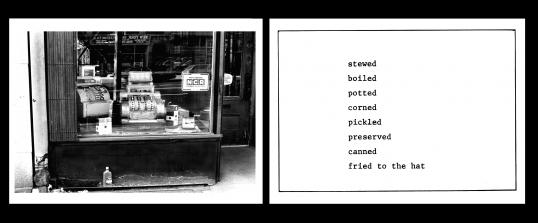

Finally Rosler finishes with an analysis of her own work: The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems. Rosler sardonically describes in this work through both photograph and text that of a world which belongs to the past. The medium used (photographs and text in a style from the 1930s) she argues should belong of the past too. That is because ‘There is nothing new attempted in a photographic style that was constructed in the 1930s when the message itself was newly understood, differently embedded’ – (Rosler, 1992) – in her own words. I would agree that this approach is dated and would tend to concentrate on ‘the ascendant classes … implied to have pity on and rescue members of the oppressed’ – (Rosler, 1992). As I understood from her text onwards photographers looking forwards can help instigate social change by analysing society that is all around us by exposing things like racism, sexism and class oppression, questioning whether ‘a radical documentary can be brought into existence’ – (Rosler, 1992). I would suggest that a visually striking and different aesthetic for photographs/bodies of work as compared to that of the 1930s or even Rosler’s own The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems would be necessary if Rosler’s encouraged approach was to work.

References:

Rosler, M. (1992). In Bolton, R. (ed.) (1992). The Contest of Meaning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp.303-325.

Szarkowski, J. (1967). New Documents. [Exhibition] 28 Feb. 1967 – 7 May. 1967. Museum of Modern Art, New York.